24 March 1603: Accession of James I

15 March 1604: James I’s Royal Entry into London

Monarchs customarily processed through the city of London with the royal entourage on the day before their coronation, although in the case of

James I the entry was delayed because of the plague. The entry was an important form of political communication: it displayed the loyalty of the political elite, while also lauding the qualities of the ruler through the iconography of the triumphal arches and the accompanying speeches which occurred at key points along the route. But tensions and rivalries between the devisers of the entry meant that

Read more >>

19 March 1604: James I’s First Speech to Parliament

King James’s first speech to his English parliament, on 19 March 1604, was his opportunity to introduce himself to his new subjects. He aimed in this speech to present an authoritative self-image, outlining his theories on kingship and tactfully setting aside four decades of

Elizabethan rule. He also sought to introduce his vision for the union of Scotland and England, to create a new nation of Great Britain. But he was also aware of tensions, over both his policies and his perception of the relation between parliament and the monarch. These tensions

Read more >>

5 November 1605: The Gunpowder Plot

The Gunpowder Plot was one of the most controversial events of the early Stuart period. A group of Catholic terrorists schemed to blow up parliament with the king and his family inside, thus removing the Stuart dynasty from the British throne. One of the most interesting responses to this moment was Shakespeare’s

Read more >>

6 November 1612: Death of Prince Henry

Prince Henry by Robert Peake the Elder, oil on canvas (c. 1610). © National Portrait Gallery, London

7 March 1623: Prince Charles Arrives in Madrid

Since 1614 negotiations for the marriage of Prince Charles to the Spanish infanta Maria Anna had been taking place. In 1623 Charles travelled incognito with the court favorite George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham. Charles and Buckingham make numerous gaffes and the match fell through. Affronted by their poor treatment in Spain, Charles and Buckingham returned home and called from a French match. On 13 June 1625 he married the French princess Henrietta Maria.

27 March 1625: James I Dies

The death of any king is a time of instability. In 1625, while the line of succession was without question,

Charles I faced considerable levels of uncertainty over diplomatic and religious policy. And, thanks to the unauthorized circulation of George Eglisham’s pamphlet

The Forerunner of Revenge, he also had to confront the allegation that his father,

King James, had been murdered at the hand of the court favorite George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham. Although there was never much foundation to Eglisham’s claims, this episode illuminates a culture of court scandal and the circulation of illicit news in the early Stuart period.

Read more >>

27 March 1625: Accession of Charles I

23 August 1628: Assassination of Duke of Buckingham

George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham,

attributed to William Larkin, oil on canvas, (c. 1616). © National Portrait Gallery

The great court favourite, George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, who rose to power under

James I and retained his position under

Charles I, was assassinated in Portsmouth by a discontented soldier called Felton. Though Felton was hanged, the act was widely celebrated by people who had resented Buckingham.

10 March 1629: Charles Dissolves Parliament

Charles I dissolved parliament in 1629 and did not recall it until 1640. This period is known as the personal rule.

1633: The Rise of Controversial Statesmen

William Laud, after Sir Anthony Van Dyck, oil on canvas (c.1636). © National Portrait Gallery.

Two of the most controversial figures of their time were promoted to senior roles in Church and state: William Laud was made Archbishop of Canterbury, and Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford, was appointed Lord-Deputy of Ireland.

1634: Ship Money Imposed

This form of taxation, which Charles believed could be levied without recourse to parliament, became a source of dispute and resentment in the years preceding the Civil War.

1637: Scotland Resists Charles’s Authority

Under the influence of Archbishop Laud, Charles tried to impose the English Liturgy on the Scots. An army was formed to resist the imposition. Although armed conflict was averted in the Pacification of Berwick in 1639, the Scots had their way on the English Prayer Book.

1640: Year of Two Parliament

The ‘Short Parliament’ was dissolved by Charles after only three weeks; however, the Long Parliament, summoned becuase of Charles’s continuing worries about finances, would remain in place for twenty years. It was by no means compliant: two of its first acts were the impeachment of Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford, and William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury.

22 November 1641: Progression to War

Parliament passed the Grand Remonstrance and presented it to Charles I on 1 December. This document listed parliament’s grievences with Charles’s rule, challenged the arbitrary power of the king, and asserted the authority of parliament.

5 May 1646: Charles Surrenders to the Scottish Army

Having escpaed the seize of Oxford, Charles travelled north and surrendeed to the Scottish army camped at Newark in Nottinghamshire. From there, the Scots moved with Charles to Newcastle and eventually sold him to the English Parliamentarian army in January 1647.

11 November 1647: Charles Escapes

In November 1647 Charles escaped his captors, fleeing to the royalist forces on the Isle of Wight. Here he renewed secret negotiations with parliament and the Scots. Charles escape initiated the second English civil war.

6 December 1648: Pride’s Purge

On 5 December parliament voted to continue negotiations with Charles I, much to the army’s dismay. The army thus decided to prevent their opponents from entering parliament. On 6 December Colonel Thomas Pride and his soldiers stationed themselves outside parliament and blocked entry to nearly a hundred MPs, arresting thirty-six. Parliament was now rigged in the army’s favour. One week later parliament voted to put Charles on trial for war crimes.

30 January 1649: The Execution of Charles I

19 May 1649: English Commonwealth Established

1 January 1651: Charles II Crowned in Scotland

Scone was the traditional coronation place of Scottish monarchs. Charles II accepted the Scottish crown and was crowned at Scone on 1 January 1651.

10 July 1652: First Anglo-Dutch War Begins

16 December 1653: Oliver Cromwell Proclaimed Lord Protector

3 September 1658: Death of Oliver Cromwell

When he died in September 1658,

Oliver Cromwell had completed an extraordinary rise to power. From being an army officer in the Civil Wars and defender of the execution of Charles I, Cromwell had, in 1653, become Lord Protector. This title invested in Cromwell supreme political power. Yet many of his enemies, and some of his former allies, saw the Protectorship as little more than a new

Read more >>

April 1659: New Model Army Depose Richard Cromwell

Cromwell’s son and successor, Richard (1626-1712), did not command the confidence of the New Model Army as his father had. After reigning as Lord Protector for just seven months, Richard was deposed by the New Model Army in the spring of 1659.

Charles II’s (1630-1685) main ally was Cromwell’s governor of Scotland, General George Monck (1608-1670), who went on to become the chief architect of the Restoration. Monck had changed sides during the civil wars. In the mid 1650s rumours circulated that he was secretly working for the Stuarts. These rumours were probably baseless at the time. But, in July 1659, Monck finally opened a line of communication with the Stuart court at the Hague. Leading his superior army south to remove the chief parliamentarians Charles Fleetwood (1618-1692) and John Lambert (1619-1684), Monck entered London on 3 February 1660. At this stage his purpose seems unclear. Monck dissolved the Rump Parliament and established a new Convention Parliament. He was effectively in control of the British Commonwealth. All this while, Charles was negotiating with Monck.

4 April 1660: Charles II Issues Declaration of Breda

1 May 1660: Declaration of Breda Presented to Convention Parliament

At Monck’s recommendation, Charles issued the Declaration of Breda. In it, he promised a general pardon for all crimes committed during the civil wars and Interregnum, for those who recognized him as the lawful king. On 1 May the Declaration was presented to the Convention Parliament, members of which proceeded to vote that ‘the government is and ought to be in King, Lords and Commons’. Parliament formally invited Charles to return to Britain and backdated his accession to the date of his father’s execution in 1649.

8 May 1660: Charles II Proclaimed King by Parliament

25 May 1660: Charles II Lands at Dover

22 April 1661: The Royal Entry of Charles II

As part of the effort to signal the return to normality at the Restoration,

Charles II staged a spectacular entry to the city of London on the eve of his coronation. But for all the emphasis in the spectacle on unity and legitimacy, it was difficult to conceal the very real ideological tensions in the city. Although Londoners had been enthusiastic about the return of the king, they had varying expectations of Charles’ rule, and disagreements soon emerged over religion. That meant that the entry of 1661 was more divisive than previous such events.

Read more >>

19 May 1662: Act of Uniformity

The Act of Uniformity was one of the most important pieces of legislation of the later Stuart era. It established the forms of public prayers, administration of the sacrament, and other liturgical practises of the established Church of England. It also prescribed a new edition of the Book of Common Prayer, which included new prayers for the Stuart royal family. Over two-thousand clerics refused to recognize these new rules and were consequently expelled from the Church of England. This led to the concept of non-conformity, which would dominate English religious and party politics well into the nineteenth century.

21 May 1662: Charles II Marries Catherine of Braganza

Royal marriages in early modern Europe were occasions to forge alliances on the diplomatic chessboard. Many queens also came to wield influence over the political, religious and cultural lives of their adopted nations. Hence the choice of bride for

Charles II, thirty years old and unmarried when he returned to Britain in 1660, was hotly debated. Catherine of Braganza, daughter of the King of Portugal, was not an obvious choice; however, she brought with her a considerable dowry, including trading rights over the port of Bombay. She is also thought to have popularized a taste for one particular exotic commodity: tea.

Read more >>

4 March 1665: Second Anglo-Dutch War Begins

2 September 1666: Great Fire of London

27 March 1672: Third Anglo-Dutch War Begins

30 September 1673: James, Duke of York, Marries Mary of Modena

Among the most steadfast supporters of

James, Duke of York, was Aphra Behn. Behn was one of the most prominent writers of the later Stuart era. In her plays, including

The Rover (1677), she addressed questions about gender and power. These themes are also present in her political poetry. During the reign of James II, Behn wrote many poems in support of the Stuart monarchy and they focus not just on the king but also the queen consorts who were central to the

Read more >>

August 1678: Titus Oates Initiates Popish Plot

In the summer of 1678 a clergyman called Titus Oates claimed to have learnt that a new Catholic plot was underway, where thousands of Catholics were going to invade Britain; they were going to slaughter Protestants up and down the country; and they were going to forcibly reinstate the Catholic Church in Britain. The plot was fabricated by Oates in an effort to stir up anti-Catholic prejudice. But people at the time believed it was true and began to concentrate their fears Read more >>

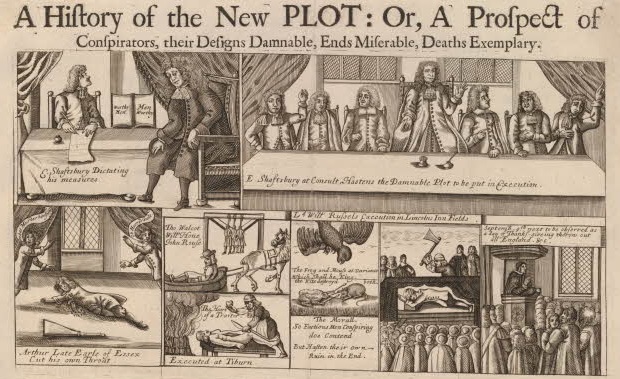

15 May 1679: Exclusion Crisis Begins

The Exclusion Crisis was a political episode that ran from 1679 through 1681. Charles’s brother and heir apparent,

James, Duke of York had converted to Roman Catholicism. In a climate intensely hostile to Catholicism, the prospect of a Catholic succession to the throne was unpopular. Thus on 15 May 1679 a faction in parliament, led by Anthony Cooper, Earl of Shaftesbury and

James Scott, Duke of Monmouth, introduced a bill in the House of Commons with the intention of excluding James from the succession. Propaganda for and against exclusion was produced on all sides for the duration of the crisis, most famously John Dryden’s anti-exclusionist satire

Absalom and Achitophel (1681). In this film

Read more >>

21 March 1681: Oxford Parliament Assembled

The fifth and last parliament of Charles II’s reign was called at Oxford in 1681. Shaftesbury and his supporters attempted to pass a third and final exclusion bill, this time presented with popular support. Charles dissolved parliament as soon as the bill was presented.

12 June 1683: Rye House Plot Discovered

The Rye House Plot was a conspiracy among an extremist group of Whigs to assassinate

Charles II. The plan was to kill Charles on his way to the horse racing at Newmarket. But the races were cancelled due to a fire on 22 March, and the hit was therefore postponed. Meanwhile an informant called Josiah Keeling passed details of the plot to the authorities. Several major Whig politicians were seized, tried, and executed, including William, Lord Russell, and Algernon Sidney.

6 February 1685: Accession of James II

6 February 1685: Accession of James II

11 June 1685: Monmouth Rebellion Begins

James Scott, Duke of Monmouth, was the illegitimate son of Charles II and Lucy Walter, daughter of William Walter of Pembrokeshire. He had been a supporter of the Exclusionists in the late 1670s. After

Charles’s sudden death on 6 February 1685, Monmouth began plotting once again with exiled British dissidents. On 11 June 1685 Monmouth landed at Lyme Regis and began to gather an army to challenge the accession of

James II. Monmouth was known as the ‘Protestant Duke’, and his supporters were universally opposed to the popish James II. By the end of June, Monmouth’s army numbered around 40,000 men and posed

Read more >>

6 July 1685: Monmouth’s Army Defeated

Monmouth‘s army was defeated at the Battle of Sedgemoor, near Bridgewater in Somerset. Monmouth managed to escape the battlefield but was eventualy intercepted and captured. He was taken to the Tower of London and executed one week later, on 15 July. Many of Monmouth’s soldiers were also captured and tried in a series of trials now known as the Bloody Assizes, in which around 1300 men were found guilty and many were executed.

10 June 1688: Birth of James Francis Edward Stuart

In the summer of 1688, Mary of Modena, queen to

James II, gave birth to a

son. This boy was the heir to the throne and his birth was celebrated by many in the country. But others were less happy about the new arrival, seeing it as ushering in the prospect of a permanent Catholic dynasty in Britain. In numerous scandalous pamphlets and prints, the royal baby was presented as an imposter, a fraudulent child smuggled into the Queen’s bedchamber in a warming pan.

Read more >>

30 June 1688: ‘Immortal Seven’ Invite William of Orange to Invade England

The ‘Immortal Seven’ were the seven English noblemen who signed an invitation to William of Orange. The invitation informed William that, if landed in England with an army, the signatories and their many allies would rise up and support him. The invitation said nothing, however, of deposing James and making William king. The seven merely wished to curb his power and perhaps set up a regency. The letter was couriered to William in The Hague by Rear Admiral Arthur Herbert disguised as a sailor, and identified by a secret code. The invitation spurred on William’s invasion plans, which he had already started.

5 November 1688: William of Orange Lands in Torbay

William III landed at Torbay with a substantial army. News spread quickly of his arrival. After a few skirmishes,

James II and his family fled to France. In this film Dr Joseph Hone and Professor Andrew McRae look at two newspapers established after William’s invasion. One of the greatest developments of the seventeenth century was the development of news. At the start of the seventeenth century there were no newspapers. By the end of the century there were many

Read more >>

13 Feburary 1689: Accession of William III and Mary II

16 December 1689: Bill of Rights

5 May 1689: Britain Declares War Against France

Prior to his invasion of England, William of Orange had been locked into a series of wars with Louis XIV of France. One of William’s principal reason for invading England was to bring English military strength to this war against the ‘exorbitant powers’ of France. Under William’s leadership England joined the Grand Alliance of protestant nations against Louis. This war became known as the Nine Years’ War and finally ended inconclusively with the signing of the Treaty of Ryswick in 1697.

1 July 1690: Battle of the Boyne

The first attempt by

James II to regain his throne occurred in Ireland. The Irish supported James because of the Declaration of Indulgence, which granted liberty of conscience to Irish Catholics. The battle between the Williamite and Jacobite forces took place on the banks of the river Boyne.

William won the battle, with the Jacobites retreating. James escaped back to France.

28 December 1694: Mary II Dies

Mary II, by Sir Peter Lely, oil on canvas (1677). © National Portrait Gallery, London.

23 February 1696: Jacobite Assassination Plot Discovered

In early 1696 a splinter group of Jacobites plotted to assassinate William III. Members of the group had been directed by James II to begin raising regiments and recruiting spies for the Jacobite court. Whether James guided them to assassinate William is unclear. Ultimately the plot was discovered and the key plotters were rounded up and executed. In the aftermath of the plot, William required all public servants to swear a new oath of loyalty and allegiance.

20 September 1697: Treaty of Ryswick

The Nine Years’ War concluded with the Treaty of Ryswick, in which the French returned most of their newly gained territories to the Allied states. Louis XIV also promised to acknowledge the legitimacy of William III and cease his support for the Jacobites. He did not keep to this promise.

30 July 1700: William, Duke of Gloucester, Dies

Princess Anne and William, Duke of Gloucester, studio of Sir Godfrey Kneller, oil on canvas (c. 1694). © National Portrait Gallery, London.

12 June 1701: Act of Settlement

The death of

Anne‘s only living child, William, Duke of Gloucester, necessitated legislation to ensure the protestant succession of the British crown.

James Francis Edward Stuart could not be allowed to succeed because of his Catholicism. Thus the Act of Settlement stipulated that, after Anne’s death, the crown should pass to her closest protestant relative, Sophia, Electress of Hanover. In this film

Read more >>

8 March 1702: Accession of Queen Anne

23 April 1702: Coronation of Queen Anne

The coronation was the most important ritual of any monarch’s life. Distinctive medals were distributed at each Stuart coronation. Expensive gold medals were reserved for diplomats and visiting dignitaries, while cheaper silver and copper medals were thrown freely into the crowd. Each medal was designed with the new monarch’s approval and established key aspects of their Stuart iconography. In this film Dr Joseph Hone and Professor Andrew McRae look at the medal designed by Isaac Newton for the coronation of the last Stuart monarch, Queen

Read more >>

4 Mary 1702: Britain Declares War Against France and Spain

Charles II, king of Spain, died in 1700 without an heir of his body. In his will he left the Spanish crown to the French prince Philip of Anjou, in direct contravention of the Treaty of Ryswick. This would create a Franco-Spanish Catholic superpower. Britain joined the protestant powers of Europe in declaring war against France and Spain in an attempt to prevent this succession.

1 May 1707: Act of Union

The succession of

James VI and I in 1603 had merged the crowns of England and Scotland. But the two parliaments remained separate. In 1707 the Act of Union was passed with cross-bench support. This Act unified Scotland and England into a single nation: the United Kingdom of Great Britain. Although England stood to gain financially from the arrangement, the principal motivation was to enforce the English Act of Settlement in Scotland. Until the Union of Parliaments, the Scottish throne could still be inherited by a different successor to the one laid out in the Act of Settlement. The Act of Union ensured the Hanoverian succession also applied to Scotland.

25 March 1708: Failed Jacobite Invasion

Many aspects of the Act of Union were economically disadvantageous to the majority of the Scottish populus. James Francis Edward seized on populist discontent in 1708 with an attempted invasion of Britain via Scotland. James had military support from France and circumstances seemed favourable. Unfortunately the Jacobite fleet was foiled as it attempted to land at the Firth of Forth. Terrible weather forced the Jacobites to adandon the invasion. Never again would the Jacobites receive such significant military support from France.

11 April 1713: Treaty of Utrecht

The War of the Spanish Succession finally ended in 1713 with the signing of the Treaty of Utrecht. Although the Whigs considered the Treaty a capitulation to France, Britain gained hugely from the peace settlement, including new territories in the Americas and in Europe, including Gibralter, and a monopoly over the lucrative Asiento slave trade. The European balance of power was now shifted firmly in Britain’s favour. Anne died soon afterm in the summer of 1714. Her final days were dominated by courtly intrigue and internal power struggles.