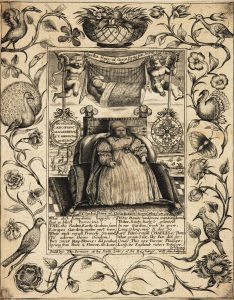

On 13 May 1629, Queen Henrietta Maria gave birth to a short-lived prince, who died within hours. Just over a year later, the prayers of both the queen and of her subjects were answered with the delivery of a healthy son, the future Charles II. His older brother, the first Prince Charles, was not forgotten, however. An engraving by William Marshall, produced to celebrate the birth of the surviving heir, depicts both Stuart babes. The living prince sits, chubby-faced, propped up on a bundle of cushions, arranged to resemble a throne. On top are plumes of ostrich feathers, which signify his position as Prince of Wales. Above lies his brother, eyes closed and wrapped in swaddling. His cradle is carried by two cherubs who support a banner proclaiming: ‘Charles Prince of Great Britaine borne, baptiz’d and Buried May 13 1629’. Here divisions between the living and the dead have been blurred and a prince, who lived less than a day, is remembered and honoured – immortalised in print. Indeed, the engraving also had an afterlife. With minor adjustments it was reissued following the births of Princess Anne in 1637 and Henry, Duke of Gloucester, in 1640. Ten years after his demise then memories of the deceased Prince Charles persisted. Death was by no means an end.

On 13 May 1629, Queen Henrietta Maria gave birth to a short-lived prince, who died within hours. Just over a year later, the prayers of both the queen and of her subjects were answered with the delivery of a healthy son, the future Charles II. His older brother, the first Prince Charles, was not forgotten, however. An engraving by William Marshall, produced to celebrate the birth of the surviving heir, depicts both Stuart babes. The living prince sits, chubby-faced, propped up on a bundle of cushions, arranged to resemble a throne. On top are plumes of ostrich feathers, which signify his position as Prince of Wales. Above lies his brother, eyes closed and wrapped in swaddling. His cradle is carried by two cherubs who support a banner proclaiming: ‘Charles Prince of Great Britaine borne, baptiz’d and Buried May 13 1629’. Here divisions between the living and the dead have been blurred and a prince, who lived less than a day, is remembered and honoured – immortalised in print. Indeed, the engraving also had an afterlife. With minor adjustments it was reissued following the births of Princess Anne in 1637 and Henry, Duke of Gloucester, in 1640. Ten years after his demise then memories of the deceased Prince Charles persisted. Death was by no means an end.

From this tale of two princes we can deduce that the business of Stuart succession was unpredictable, marked by biological accidents, both strengthening and threatening. The birth of a prince promised dynastic security and political stability; with his premature death, a supporting prop was lost. Yet, despite the uncertainties of early modern reproduction and family life, the Stuarts persistently promoted dynastic and domestic images to reinforce royal authority. When James VI and I crossed the border to claim his new throne in 1603, his subjects greeted a ‘father king’. Over a century later, Queen Anne would employ maternal symbolism to represent her sovereignty.

The literal parenthood of both monarchs was precarious though. Five of James’ children were to die prematurely, including his heir, Prince Henry, while Anne was to suffer repeatedly the misfortune of miscarriages and still-births. This tension between representation and reality has long preoccupied my research and, as an art historian, I am particularly interested in how relationships between the symbolic and the actual were negotiated visually. Until now, literary studies have led the way in interrogating the representation of family as a political metaphor – surprisingly few art historical analyses have been attempted. As I have probed Stuart dynastic propaganda further, I have discovered a body of intriguing and idiosyncratic images, produced at moments both of crisis and continuity.

My book, Imaging Stuart Family Politics: Dynastic Crisis and Continuity, is the result of this research. It examines the evolving portrayal of royal dynastic and domestic ties, across the long seventeenth century. From conception onwards, offspring were presented to their subjects through texts, images and public celebrations. Audiences, in turn, were exhorted to share in their development, establishing emotional bonds with the ruling family and its latest additions. Possession of a poem or a print celebrating a birth or a coming-of-age brought the owner closer to the Stuarts, bridging the distance between subject and royal.

My book, Imaging Stuart Family Politics: Dynastic Crisis and Continuity, is the result of this research. It examines the evolving portrayal of royal dynastic and domestic ties, across the long seventeenth century. From conception onwards, offspring were presented to their subjects through texts, images and public celebrations. Audiences, in turn, were exhorted to share in their development, establishing emotional bonds with the ruling family and its latest additions. Possession of a poem or a print celebrating a birth or a coming-of-age brought the owner closer to the Stuarts, bridging the distance between subject and royal.

Yet inviting the public into royal domestic affairs also exposed them to intense scrutiny and private interactions were endowed with public dimensions. Reproductive disappointments, domestic quarrels and family tragedies were national concerns and popular reactions could endorse or challenge dynastic messages. Visual display played a vital role in these dialogues and images of Stuart fathers, mothers and offspring all had the power to support or complicate monarchical power.

I hope that my book will encourage scholars to reconsider the significant part of the visual in Stuart politics and to reassess a body of fascinating material which performed a crucial, if, at times, unpredictable, role in early modern public communication.

Catriona Murray is Lecturer in History of Art at the University of Edinburgh. Imaging Stuart Family Politics: Dynastic Crisis and Continuity is published by Routledge, as part of its Visual Culture in Early Modernity series.